Real Madrid: Why The White House Needs To Be Revamped

In-depth statistical and tactical analysis of Real Madrid out-of-possession performances, especially in big clashes where Carlo Ancelotti's team had underperformed.

"Synergy is everywhere in nature. If you plant two plants close together, the roots commingle and improve the quality of the soil so that both plants will grow better than if they were separated. If you put two pieces of wood together, they will hold much more than the total weight held by each separately. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. One plus one equals three or more." ~ Stephen Covey

Once Ralf Rangnick, Austria national team manager, said, “A little bit of pressing is like a little bit pregnant. Either you are pregnant or not. Either you want to play pressing or not. But please, not a little bit of pressing.”

With Carlo Ancelotti, Real Madrid is a little bit pregnant. They go high up the pitch with the intention of intensely pressing. However, the execution has nothing to do with the intended objective.

Take this scene against Arsenal at the Emirates Stadium.

David Raya slides a pass to the inverted Lewis Skelly as if there weren’t Vinícius Júnior and Kylian Mbappé leading the pseudo-press. The Spanish goalkeeper is already at the forefront of the matter.

None of the front two closes off the central access, allowing Lewis Skelly to receive in acres of space and break down Real Madrid’s first line by a simple pass.

The same scene replicated itself against AC Milan in the UCL group stages. However, the frailty is in midfield, as AC Milan created an overload through Pulisic dropping deeper. Whatever Real Madrid’s players do here, AC Milan would progress.

If Camavinga shuts down Fofana, Maignan would clip the ball over the top to Pulisic. If Bellingham shifts to press Pulisic, Maignan would pick out Emerson near the flanks.

It's a lose-lose situation.

Only players cannot be blamed without returning to Real Madrid's out-of-possession structure. By doing so, it resulted that the man in the dugout, Carlo Ancelotti, cannot be taken out of the equation and would also take his part.

In this piece, we analyzed Real Madrid's out-of-possession performances from a statistical and tactical perspective, focusing more on Los Blancos’ big clashes to shed light on Carlo Ancelotti’s strategies to deal with teams on the same level as his.

📊 Statistical analysis

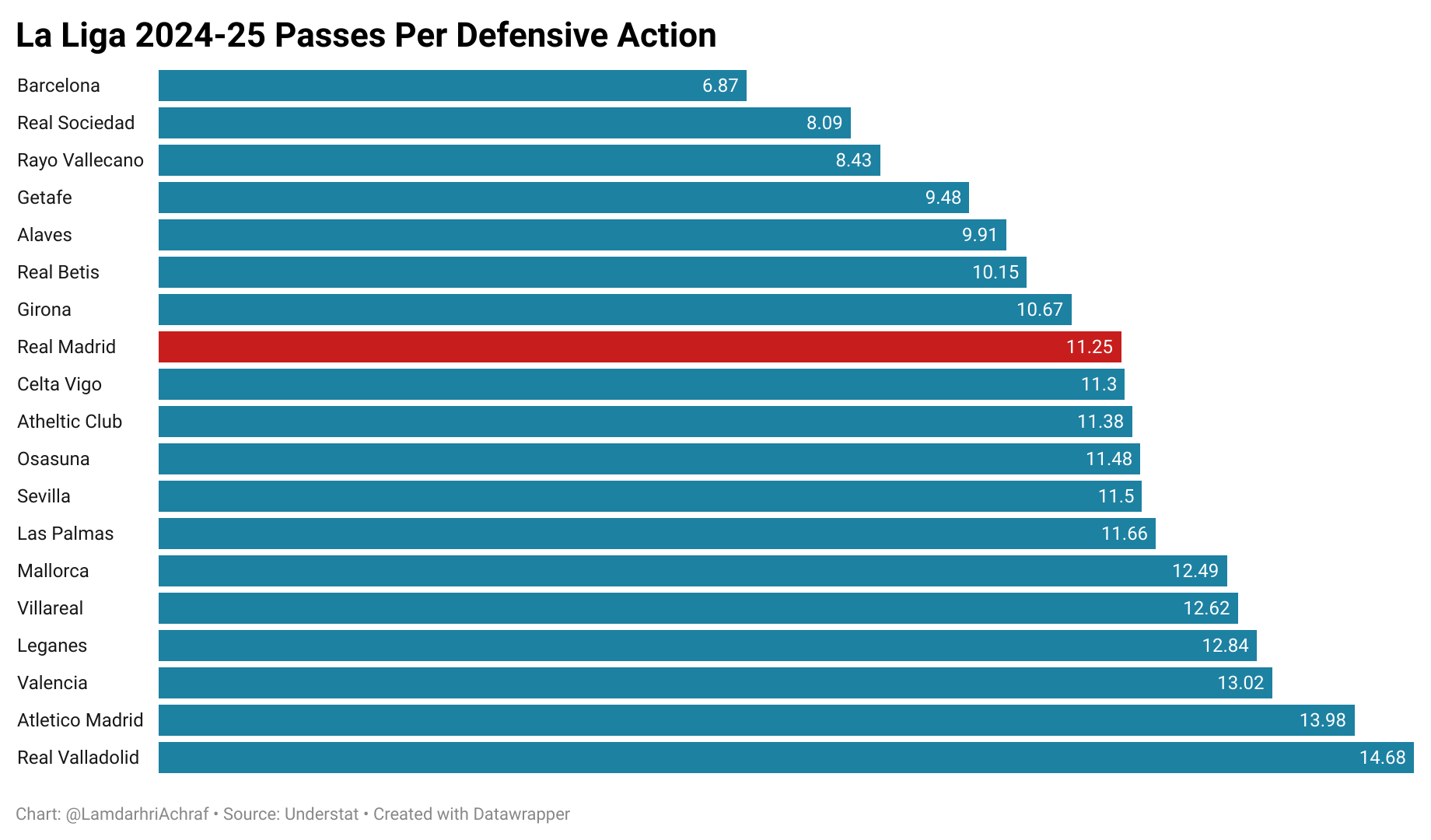

In general, Real Madrid averaged 11.25 passes per defensive action in the final third. Carlo Ancelotti’s team allowed 4.38 PPDA more than their direct rivals in La Liga, Barcelona, who suffocate the opposition, enabling them only 6.87 PPDA. Analyzing Real Madrid out-of-possession statistics without looking at the name hints at the first glance that these numbers concern a mid-table team.

To highlight more Real Madrid defensive deficiencies, let’s take a look at opponents’ buildup disruption stats.

Until the day of writing, Real Madrid’s opponents complete 83.47% of their passes outside the final third. Comparing this number to Barcelona, it appears that the intensity of both teams’ press is night and day, as the Catalans’ opponents completed just 73.65% of their passes outside the final third, the fewest number in the league, which means that Barcelona are much more efficient when pressing high up the pitch.

Staying from the same perspective, Barcelona ranks third in terms of where the opponents lost possession when they were pressed by Hansi Flick’s men. Usually, Barcelona drives the opposition to lose the ball in more dangerous zones (27.32) while Real Madrid underperforms in this regard with 20.65. That means Real Madrid is less efficient in making their opponents play unsuccessful passes, lose dribbles, or touch the ball badly near their goal.

Keep in mind that Los Blancos are Barcelona's direct rivals for La Liga’s title.

In the UEFA Champions League, Real Madrid amassed 20.9 expected goals allowed (1.61 per game), more than any team qualified for the quarterfinal (Real Madrid played two more games in the play-off against Manchester City).

This defense cannot bring the Sixteen to Santiago Bernabeu’s museum.

👉 High-Press

To begin with, Real Madrid are passive when pressing high up the pitch. The pressing structure usually lacks quality, synergy, synchronization, and compactness. Adding to that, lethargy while working off-ball hinders Real Madrid and makes it very difficult for the team to disrupt the opposition's buildup, let alone regain the ball close to goal and capitalize on turnovers.

Here, against AC Milan, Real Madrid presses high up the pitch in a 4-4-2 formation, in which Kylian Mbappé initiates the press with a curved run. Vinícius Júnior stands still with Youssouf Fofana. Behind Valverde and Bellingham engage with the opposite fullbacks, Aurélien Tchouaméni jumps on Tijjani Reijnders, and Luka Modrić follows Christian Pulisic, who drops deeper.

The structure is perfect to trap AC Milan wide, but screams good execution. As Kylian Mbappé starts his arced run, Vinícius Júnior, without any spatial awareness, intends to jump onto Malick Thiaw, leaving Fofana to gain separation and afford the goalkeeper a free passing option to access the center-back who has been shut down by Mbappé closing the passing lane between him and the goalkeeper.

As the sequence develops, similar problems occur, with the same members repeating the same mistakes or lethargically committing to the off-ball phase. At the start of the sequence, Vinícius Júnior opened up the passing corridor, enabling the third-man combination. As Fikayo Tomori receives the ball, Mbappé nonchalantly gives up following Fofana despite the distance being so close. As a result, Valverde’s effort to close access to the wide channel was thrown down the drain, and AC Milan keeps threading passes, generating numerical superiority as they progress.

During Carlo Ancelotti’s second tenure, playing against Real Madrid’s high press is a walk in the park. Passing lanes are available for the opposition to connect passes. Wrong body positions and angles streamline opponents' buildup and progression. As aforementioned in the previous example, Real Madrid's pressing structure from a static position—when the opposition plays a goal kick—is generally acceptable. However, as the sequence starts, everything that follows renders Real Madrid vulnerable.

From an open-play situation, Carlo Ancelotti’s men display nothing more than chaotic, lethargic, and primitive press. Nothing reflects the quality at the Italian coach’s disposal.

Here, Real Madrid forces AC Milan to play the ball backward. Thus, Rossoneri has to recycle possession, finding ways to work the ball out. Nonetheless, Los Blancos have their say.

From top to bottom, the press is shoddy. Vinícius Júnior initiates the process with a wrong run and a flawed body position that keeps the passing lane between Mike Maignan and Malick Thiaw open to slice the pass. Behind, Real Madrid’s double pivots close off access to the central corridor. However, AC Milan generates an overload in the middle of the park. That is because Real Madrid commit five players at the backline to keep tabs on four cogs from AC Milan.

They have an extra man for the sake of creating a numerical superiority.

As a result, Malick Thiaw clips the ball to Alvaro Morato, who comfortably controls it and lays it off to the free Christian Pulisic between the lines, forcing Real Madrid to retreat.

Throughout the game against AC Milan, Christian Pulisic was a nightmare to Real Madrid's high press. He kept dropping deeper and freely patrolling, streamlining his team’s initial phases’ operations.

Carlo Ancelotti’s team looked unable to react to Pulisic's deeper movements. Lack of tactical tweaks and adjustments was prevalent and apparent in Real Madrid’s players’ actions.

The fifty-second minute is a prime example to shed light on Los Blancos’ fragile high press. Vinícius Júnior and Kylian Mbappé took charge of the opposite center-backs. Bellingham and Brahim Diaz chased AC Milan’s fullbacks. Coming to midfield, it is clear as day how much this team’s high press is redundant, primitive, and naive.

AC Milan generated the numerical, positional, and spatial superiority to take the ball up top.

The most efficient way for AC Milan was to progress through the central channel, as Real Madrid allowed them to (large distances to cover + numerical superiority).

On the other side, instructing one of the center-backs to stick with and track Pulisic could have neutralized AC Milan's buildup.

Under Carlo Ancelotti, especially in big games, the team looked feeble off-ball; opponents exploited the white house's lack of vertical compactness to a degree that it only required the minimum effort from the opposition side to walk through Real Madrid's block.

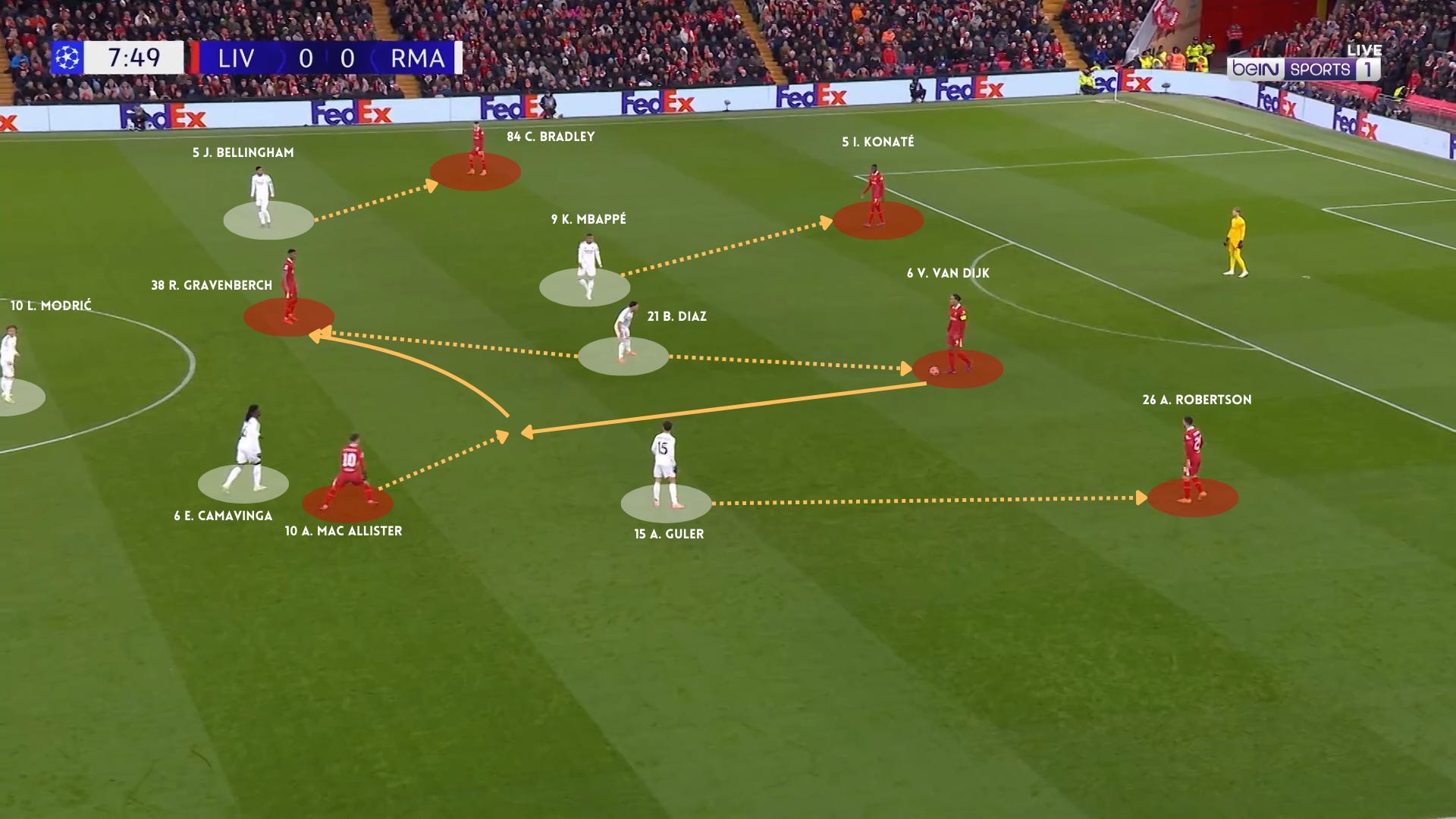

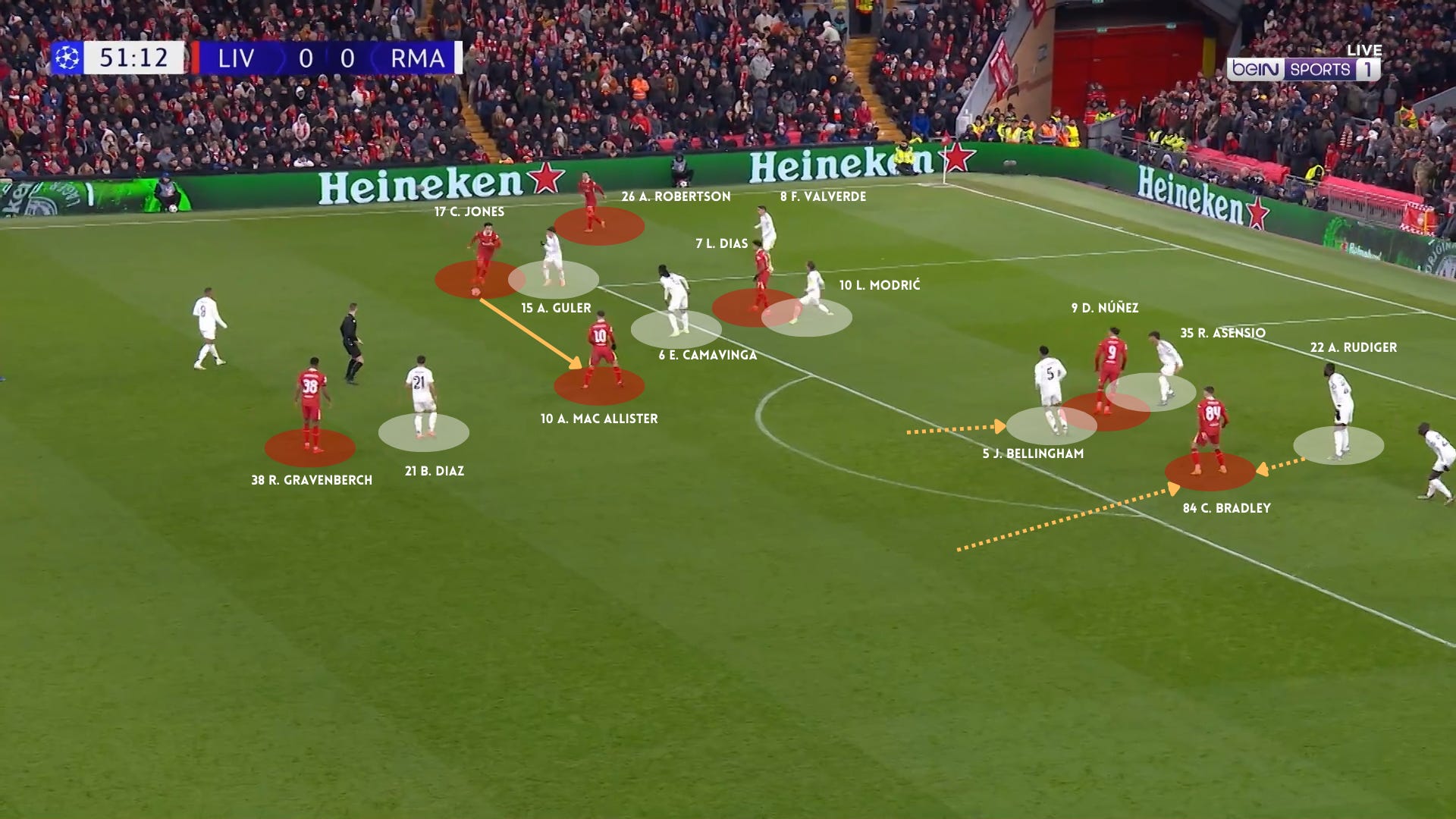

Here, Liverpool builds in a 4-3-3 shape, in which Jude Bellingham and Arda Güler take charge of the Reds’ fullbacks. Kylian Mbappé and Brahim Diaz are tasked with keeping position between the center-backs and Ryan Gravenberch to deny central access. Behind, Luka Modrić and Eduardo Camavinga man-marked Liverpool central midfielders.

Real Madrid's set-up was enough to do the job, had Camavinga not lost concentration and enabled Mac Allister to drop off to combine as the third man and find Ryan Gravenberch in the middle of the park. As the Dutchman received, Real Madrid's midfield was overloaded, similar to what AC Milan had attempted to do, making Christian Pulisic the spare player when he came deeper.

Here, Curtis Jones and Ryan Gravenberch secured the numerical superiority against Luka Modrić to take the ball up the field.

Against Arsenal, Real Madrid allowed 17.7 passes per defensive action. They almost permitted the Gunners to connect passes as if they were on a training ground. Carlo Ancelotti and his players didn’t offer anything to disrupt Arsenal's buildup phases.

The North Londoners are among the top five teams in the Premier League with a high rate of pass completion during initial phases. 86.5% of their passes are completed successfully outside their final third. They are well-drilled in taking the ball upward. Thus, opponents must be urgent, clever, intense, and fully committed while pressing Arteta’s boys to delay their attacks or to force them to play an uncomfortable game.

Neither the players did enough to disrupt Arsenal’s attack construction, nor did Carlo Ancelotti react to adjust the structure of his team. Taking this scene, the Gunners overload Real Madrid in the buildup. Not only that, but Los Blancos appeared clueless and were running out of solutions to respond to Lewis-Skelly inversion and Mikel Merino dropping out as a false.

It is a cascading effect that resulted in Arsenal progressing through as if they walked into a park, and Real Madrid's lines getting gradually dissolved with the players being outnumbered throughout the sequence. At the beginning, Camavinga and Bellingham went to press one player, Martin Ødegaard, who came deep. That resulted in negative repercussions for Rodrygo.

Thanks to Real Madrid's primitive press, Arsenal generated a numerical superiority with Kiwior, Declan Rice, and Lewis-Skelly overloaded the Brazilian in a large space where the trio could thread passes to progress, or as Lewis-Skelly did. He checked his shoulders, reading Rodrygo’s movement—Real Madrid’s winger tended to close the passing lane between Lewis-Skelly and Kiwior—and burst into space to access Declan Rice. As a result, Gabriel Martinelli was in a one-versus-one situation against Valverde. Arsenal's left-winger drove toward the byline and cut the ball back.

The fifty-first minute of the first leg against Arsenal sheds light on Real Madrid’s self-destructive mechanism when they press high up the pitch. Kylian Mbappé succeeded in driving the Gunners wide. The rest of the team followed. Camavinga tracked Ødegaard near the flanks, and Luka Modrić chased deep Mikel Merino. However, Vinícius Júnior misread the situation, letting Thomas Partey free to offer support as a spare player.

As a consequence, Arsenal got out of Real Madrid's trap, executing a third-man combination through which they accessed the underloaded side of the pitch. Saliba had acres of space to carry the ball, forcing Carlo Ancelotti's team to retreat.

To conclude this chapter, the most surprising stat about Real Madrid's defensive frailty is that they accumulated just 14% of their high-intensity pressures in Arsenal’s defensive third. In numbers, they averaged approximately 37 high-intensity pressures in the final third, the fewest by any team in a knockout stage game this season (ranked 72nd out of 72).

They press high for the sake of being high in the final third. And, when they retreat, opponents find joy in pulling them out of position via deception, countermovement, overloads, positional, and individual superiorities.

👉 Medium Block

Sitting in a medium block has been nothing more than a total disharmony for Carlo Ancelotti’s team. Real Madrid’s players are easy to pull out of position, draw their block up, and allow the opposition territory behind the backline to exploit.

The same off-ball mistakes are repeatedly committed, which threaten the team’s defensive integrity. The attack before the corner that led to AC Milan's first goal is a prime example to highlight Real Madrid's defensive frailties when laying in a medium block.

The white team defends in a 4-4-2 shape in the middle third.

Álvaro Morata freely drops outside Real Madrid’s block to collect Fikayo Tomori’s pass. Morata's deeper movements create a numerical advantage against Tchouaméni, who is outnumbered by the Spanish striker, and Reijnders, who advances between the lines.

In the meantime, the latter keeps luring Éder Militão to draw him up, and Rafael Leão surges forward behind Lucas Vázquez.

In big games, teams usually put Real Madrid under scrutiny.

In fact, it makes sense when two teams of the same caliber clash and keep hitting each other back and forth, whereas the main battle is in the dugout where both teams’ coaches respond to the other’s tactical tweaks, trying to maintain or give their teams the slightest edge possible to gain the upper hand.

Especially in the 2024-25 season, Real Madrid, under Carlo Ancelotti, appeared toothless, short of solutions, and unable to react. To add insult to injury, Real Madrid accumulated the highest (the worst) rate in terms of expected goals allowed (20.9 xGA) in the Champions League. Per game, they average 1.607 xGA.

Against AC Milan, Paulo Fonseca, the Rossoneri's former head coach, put Real Madrid’s defensive block to the test. To elaborate, Theo Hernández had clear instructions to push up, forcing Valverde to drop off. On the right side, Emerson stood still to tie Jude Bellingham, with the front two being dragged by the opposite center-backs. As a result, AC Milan created a numerical superiority as Christian Pulisic tended to stroll freely.

Before Vinícius Júnior approached Malick Thiaw (above), AC Milan had already gained the advantage. The Brazilian winger, revealing his intentions, furnished AC Milan’s road with flowers to walk through. As Vinícius Júnior closed the gap with the ball holder, he intended to jump onto Thiaw from the right side, leaving the passing lane into Fofana accessible. After the latter received the pass, it was an easy task—as if they practiced a friendly rondo drill in a training ground—to fulfill in order to get the ball to Yunus Musah near the flank.

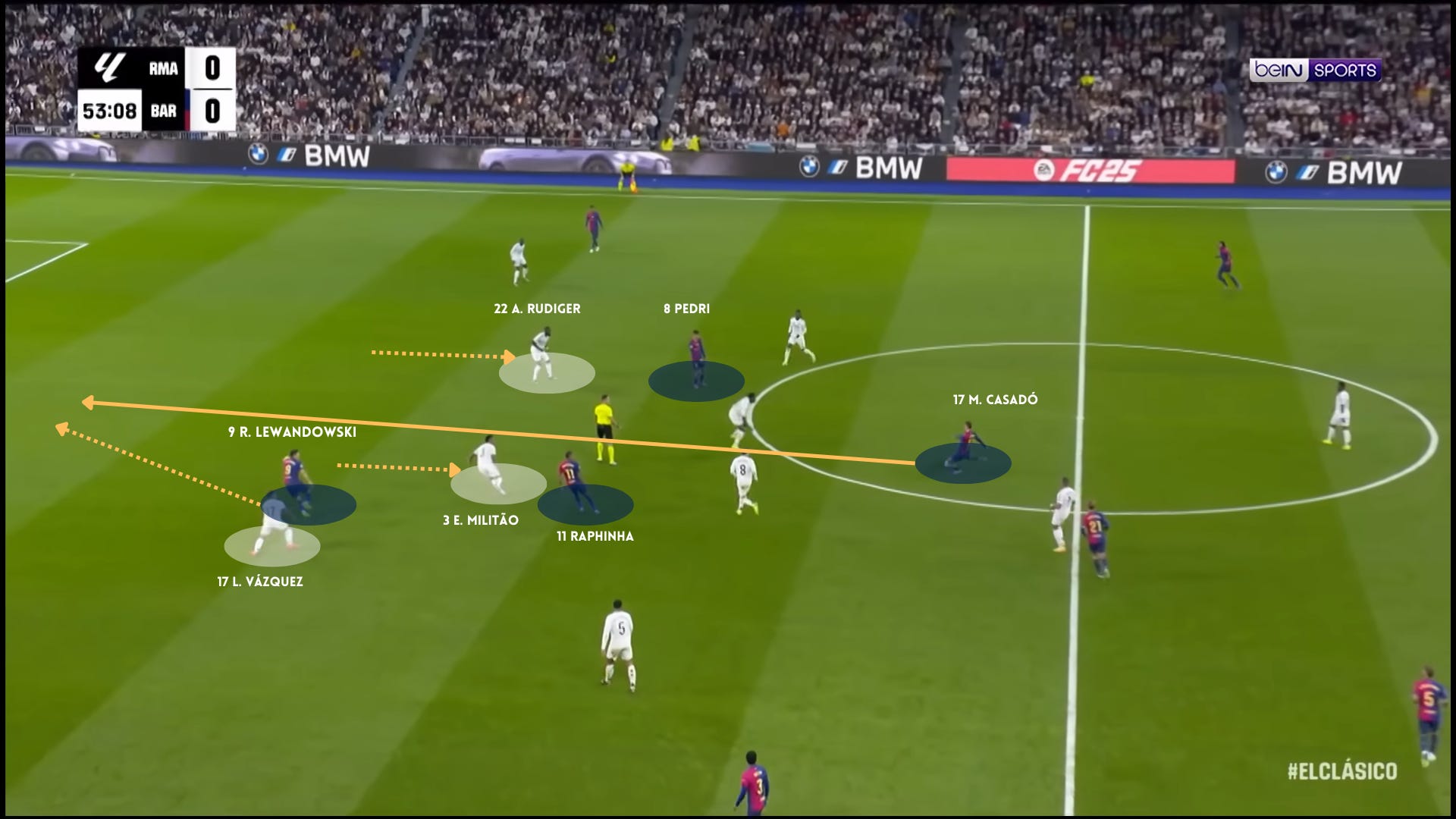

Here, Barcelona dwarfed Real Madrid on their turf through a pull-and-run pattern. Raphinha and Pedri succeeded in magnetizing Militão and Rüdiger into jumping forward and consequently pulling them out of position, creating space for Lewandowski to exploit behind the backline.

The dwarfing continued when Barcelona tarnished their rivals in the Spanish Supercup final. Hansi Flick’s men toyed with their archenemies, deceiving them to generate space inside and behind the white team’s block.

In this example, Gavi shifts across to drag Camavinga with him and opens the inside passing lane for Jules Koundé to slide the diagonal pass to Lewandowski. Not only that, but Gavi's lateral movement vacates territory between the lines for the Polish striker to come short.

Again, Lewandowski pulls Antonio Rüdiger out of position, drawing him up and allowing Lamine Yamal to race out into space and score Barcelona’s equalizer.

👉 Low Block

Against teams of the same caliber, Carlo Ancelotti tended to adopt a more conservative approach. He ceded possession, retreating and waiting to counterattack to take advantage of his front players’ speed in racing.

In fact, after the first leg of the Arsenal game, the Italian coach stated that compactness has been a major problem, which hindered Real Madrid's plans for their subsequent actions. They neither defend well deep nor are they able to counter when they face a team with an organized structure to counterpress and a well-sorted rest defense.

Against Liverpool, Real Madrid sat in a 4-4-2 low block. Arne Slot, renowned for his tactical tweaks throughout the game, made his winger, Luis Diaz, drop behind the white team’s block and allowed Curtis Jones freedom to roam. These tactical refinements disrupted Real Madrid’s defensive integrity.

Here, Luis Diaz steps down, drawing Arda Güler’s attention. Curtis Jones creeps between the lines, pulling Valverde out of his position. As a result, Andrew Robertson has room down the wide channel to push on. In addition, Jones and Diaz's off-ball movements stretched the left-inside channel for the unpressurized Virgil Van Dijk to slice open Real Madrid’s defense.

Luis Diaz and Curtis Jones were disturbing members of Real Madrid’s defense. The duo and Andrew Robertson's positional rotations infinitely generated for one of them, space behind the backline to cut through Carlo Ancelotti’s team, which appeared clueless and got caught like a deer in headlights.

In this scene (below), Luis Diaz acts as a magnet to pull out Federico Valverde. As a consequence, Curtis Jones is able to head into the gap between the center-back and the right-back, taking advantage of Luka Modrić's lateness in the tracking to receive in free space.

A dummy movement from Luis Diaz, a subpar passing lane coverage from Arda Güler, Modrić being behind time, and Camavinga's lack of spatial and positional awareness enabled Robertson to take four players out of the game with a simple pass, breaking down Real Madrid’s lines.

In this fixture, Liverpool averaged 2.8 xG and a field tilt of 62.7%. In the second half against Real Madrid, Arne Slot turned his team to attack in a 3-2-5/3-1-6 formation. The telos was to force Mbappé’s teammates backward, as it was clear in the Reds’ first goal.

In this sequence, Liverpool fullbacks push on, with Andrew Robertson wide and Conor Bradley inverting. The latter’s advanced position obligates Bellingham to drop deeper. Adding the front three to the mix, Arne Slot’s team has five players against four. That forced Luka Modrić to join the backline to keep tabs on Luis Diaz. Arda Güler does not put much effort into preventing Curtis Jones from cutting inside. Moreover, Camavinga focuses on the ball and covers zonally, which leaves Mac Allister free to receive.

As aforementioned, Liverpool attacking in numbers pushed Real Madrid's lines deeper and vacated the edge of the box for the Reds to rip apart the white house.

To elaborate, Conor Bradley stealthily came short, creating separation with Antonio Rüdiger, and Bellingham jumped onto Mac Allister. A one-two combination between Bradley and Mac Allister set free the latter in the space evacuated behind Rüdiger and put him in a position where he lashed the ball home.

Spaces are everywhere within Real Madrid’s block. They do everything in defense except form a compact block. Off-ball performances were nothing more than awful and suboptimal throughout the season. In big games wherein the quality of the personnel is even, Carlo Ancelotti’s eleven players on the pitch gave up too much space.

In a nutshell, they defended similarly to novices without a coaching trace.

In this example against Arsenal, the sequence started when Martin Ødegaard stepped behind Real Madrid’s unit, took the ball, and carried it forward, pushing Los Blancos backward. In the meantime, Bukayo Saka sniffed the space between the lines. Thus, he narrowed inside, leaving room for Jurien Timber to fly.

Consequently, Alaba was outnumbered. As a reaction, Antonio Rüdiger left his place and jumped late onto Saka. Mikel Merino, as a false nine, darted behind in the vacant space. Fortunately, Saka’s service was out of Merino’s reach.

👉 Defensive transitions

Covering the central corridors seems to be a myth for Real Madrid. Also, their distribution in possession does not allow them to counterpress to halt or delay the counterattack they are conceding. Players are distant from each other. Thus, regaining the ball in counterpress situations is significantly impossible.

Take this example below.

Kylian Mbappé cuts inside without awareness or knowledge of what's happening behind him. Mohamed Salah dispossessed him to initiate Liverpool's counterattack. Once Darwin Núñez received the pass, Camavinga, Luka Modrić, and Mbappé surrounded him. However, their effort lacks the intensity to halt the transition. Here, Real Madrid opts for two center-backs for the rest defense’s mission.

As Núñez breaks down Real Madrid's defense, he combines with Salah, who is pressed by Antonio Rüdiger, whose lateral movement expanded the central corridor for the Uruguayan striker to keep going forward, as Raúl Asencio cannot sweep to cover because Luis Diaz is pinning him. Thus, Núñez has acres of space in front of him, wherein Salah put the latter in one-versus-one against the goalkeeper. A back-to-back heroic action from Courtois and Asensio cleared the ball out of the line and saved Real Madrid from conceding.

Takeaways

Real Madrid usually makes up for their defensive frailty with their individual brilliance to win games. Besides that, nothing is working when the ball is in the opposition’s feet.

It becomes clear that neither the manager is able to make his team press with intensity high up the pitch and defend in a compact shape, nor are the players fully committed during off-ball phases.

Lethargy and nonchalance prevail over synergy and commitment.

NB: all the statistics are as of 4-15-2025. All data sources are mentioned under the visualizations. Also, I’m indebted to Markstats for the quality of the work he provides, Please take a look at his website: https://markstats.club/

If you’re enjoying what we are producing—whether it’s an analysis, scouting, or opinion—Please subscribe, leave a comment, and drop a like. It helps us know that people out there value the work, and it boosts us on the Substack algorithms.

“Sharing knowledge is not about giving people something, or getting something from them. That is only valid for information sharing. Sharing knowledge occurs when people are genuinely interested in helping one another develop new capacities for action; it is about creating learning processes.”~Peter Senge

Great piece as always mate.

Great analysis; many thanks!

One minor point - Arsenal are a North London team, not West London